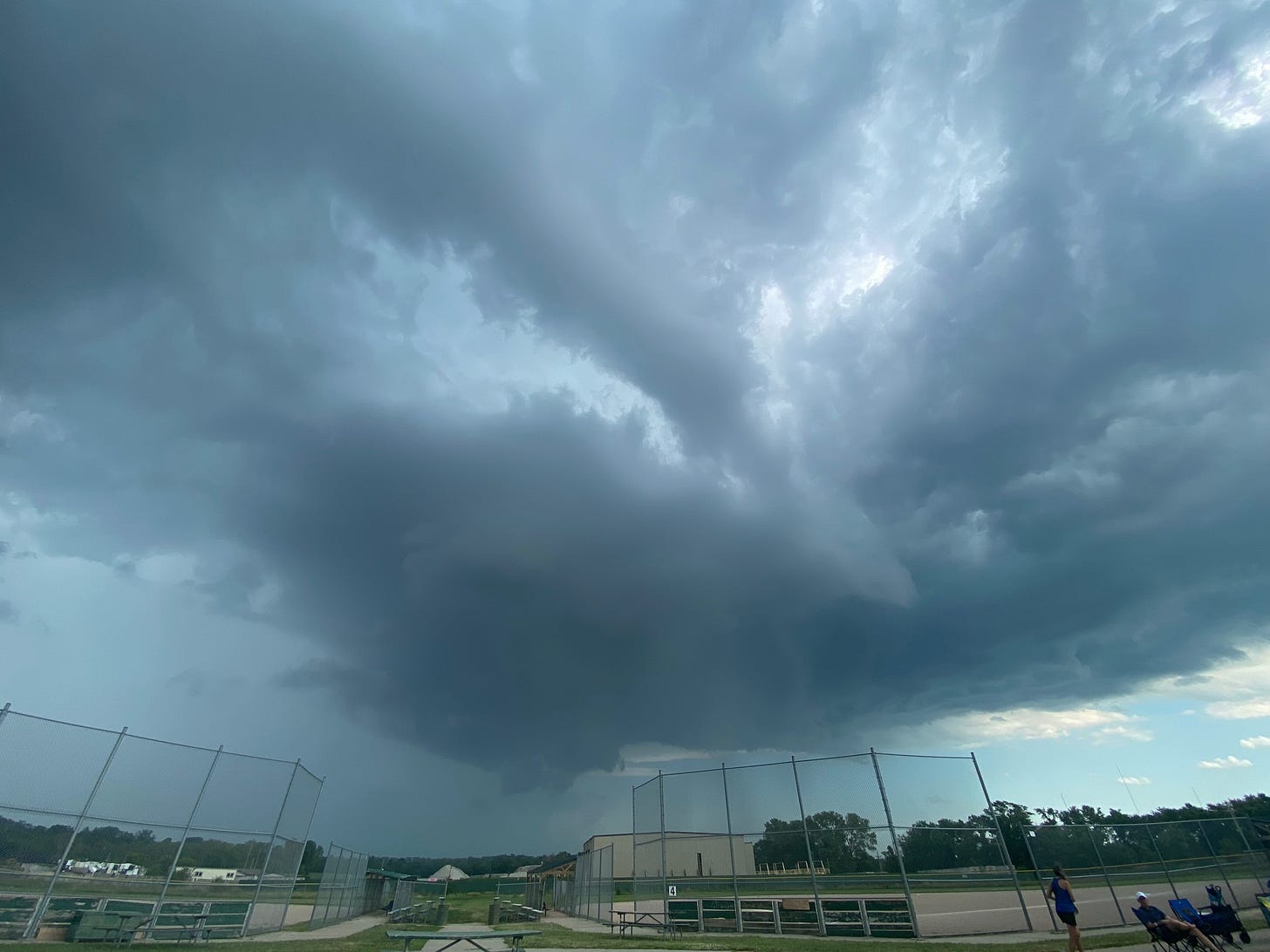

With a radar app on my phone, I checked nervously again from the visitor parents’ section at the baseball field for my son’s evening game. One shower had bypassed us with just a few drops and lightning juuuuuust a little bit outside the radius of concern around us, and the boys were on the field warming up. But the towering clouds developing practically overhead had us nervous. My husband (also a meteorologist, and also one of our team’s coaches) and I caught eyes, shook our heads at each other. We’re not getting this game in.

Rain drops started again, fatter, faster. The coaches called the boys to the “dugout” (just a covered bench area), and parents gathered to stay out of the rain. I jogged over to the opposing home-field coach (to whom I had introduced myself when we arrived), who was also huddled with his team under the shelter of their bench. I told him the next storm was developing right over us and strengthening. Our boys would be waiting in their cars. He didn’t have the authority to call off the game, but he was waiting for the league leader to make the call.

By now it was pouring. Our team — the Gretna Thunder, as irony would have it — dashed to our cars to wait for the call. We were not optimistic about playing the game. The field would be too wet. There was now lightning. I noted with worry that the home team was still under the canopy of their bench, rather than dashing to their cars. We watched every scan of radar come in, a distinct hail core now showing up right over us. Could be golf ball size hail in that core, easily. Why wasn’t it hailing yet?

Tink.

Tink tink tinktinktink.

Well, now it was hailing. Our head coach texted us all and said they’d officially called off the game, but most of us were backing out before we got the text. The game of the night had changed, from “play ball!” to “will we play baseball?” to “will we get pounded by large hail?” to “how fast can we get out of here?”

Tink tink THUNK.

Uh oh.

THUNK THUNK.

THUNKTHUNKTHUNK.

Our cars scattered in all directions, some finding shelter near trees, others diving south to try to get out of the storm. One family found a man huddling under a tree and took him into their car.

Being a storm-chasing family, a few hail dents don’t bother us. In fact, they can be hard to distinguish from the old dents, and we take some pride in them. And we are used to the hammering of hail on a car roof. But most parents’ cars were more pristine, they and their children rattled by the relentless pounding of hail on their cars. Most parents’ cars had souvenirs of the hail storm in the aftermath. Most parents don’t welcome the dents as a badge of honor. And while our family didn’t go from THUNK to BONK BONKBONKBONK, a few of our parents did drive under the worst of the stones.

We dove south out of the hail core. Stopped at a red light, the hail now to our east, we spotted large stones on the grassy strip near the road, and I hopped out of the car to pick one up, soaking my sandals in nearly ankle-high water draining in the gutter as I did.

Forget a baseball game. We had baseball-sized hail.

Hail Safety

Hail hurts, you all. It’s like having someone throw rocks at you, hard, and sometimes with rather large rocks. It can cause concussions, bruises, and broken bones. Its size can ramp up rapidly. Do not be Laura and Almanzo Wilder’s neighbor in De Smet in The First Four Years, opening his door to grab a stone while the hail is still falling, only to be knocked out by another falling stone and dragged inside by his wife, who probably was muttering, “I told you not to go out there!”

Our baseball-hail encounter occurred while we were in our cars. Hail safety when at home is pretty straightforward: stay inside until the hail passes, and stay back from the windows, especially on the wind-facing side if it’s gusty out. In cars, it’s a little scarier. You’re almost but not quite sheltered, almost but not quite safe. It’s often hard to see as rain and hail pour down. And it’s so noisy. A quarter-size hailstone sounds every bit as loud as a hammer thunking on the roof of the car. The blinding, deafening surge can cause panic.

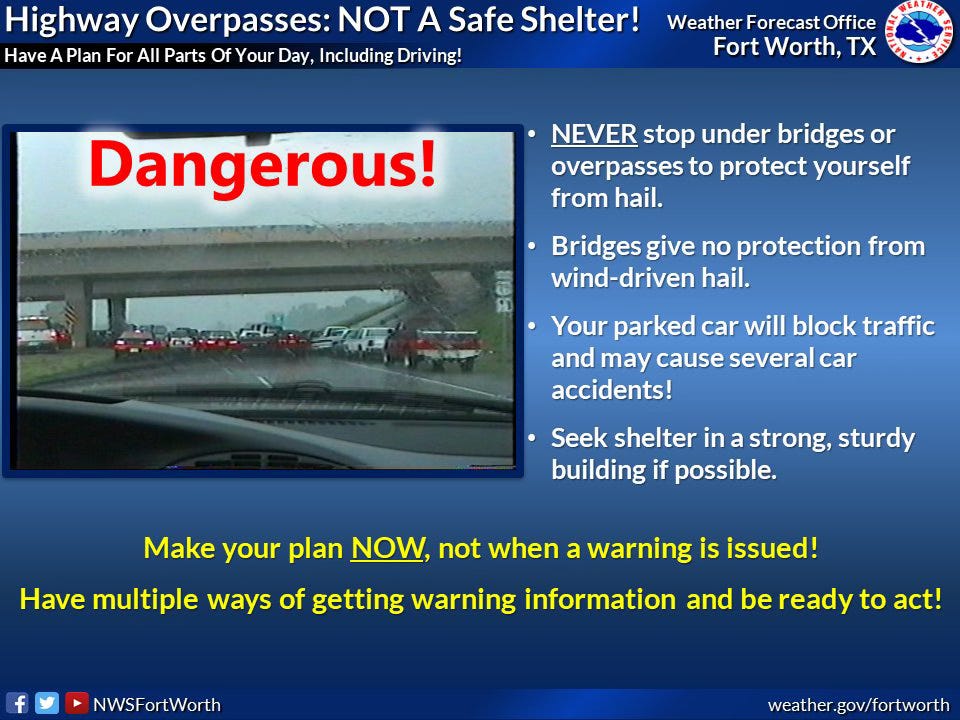

One piece of safety advice is the same: If you cannot get your car inside somewhere that is out of the elements (like a garage), stay in your car. You’re safer there than outside getting pounded by hail, even if you think you’re just dashing a short distance to a building. Pull over if you can, if and only if you can get completely off the road. I cannot stress this enough: NEVER stop on the road in the driving lane. You’re a danger to yourself and everyone else on the road if you do.

Here are a few more pro tips for weathering a hailstorm in your car.

If it’s a windy hailstorm, turn your car so that you are pointing toward the oncoming wind. Your windshield is the safest window in the car, with shatter-resistant glass. It will take the pounding hail much more safely than the side and rear windows. Yes, the windshield might get spider cracks, but that sure beats a lap full of glass from shattered side or rear windows.

Use whatever you have to put between you and the windows - an extra sweatshirt, a road map, a backpack - anything. Hold it over you or hold it up between you and the closest window. Squeeze toward the middle of the car and away from the windows.

Carry duct tape and plastic wrap in your car’s emergency kit, especially on longer trips. If you do end up with a shattered window, you can patch it up, then more safely (and comfortably) get the car somewhere for repairs.

How the Hail?

What makes hail so big in some storms?

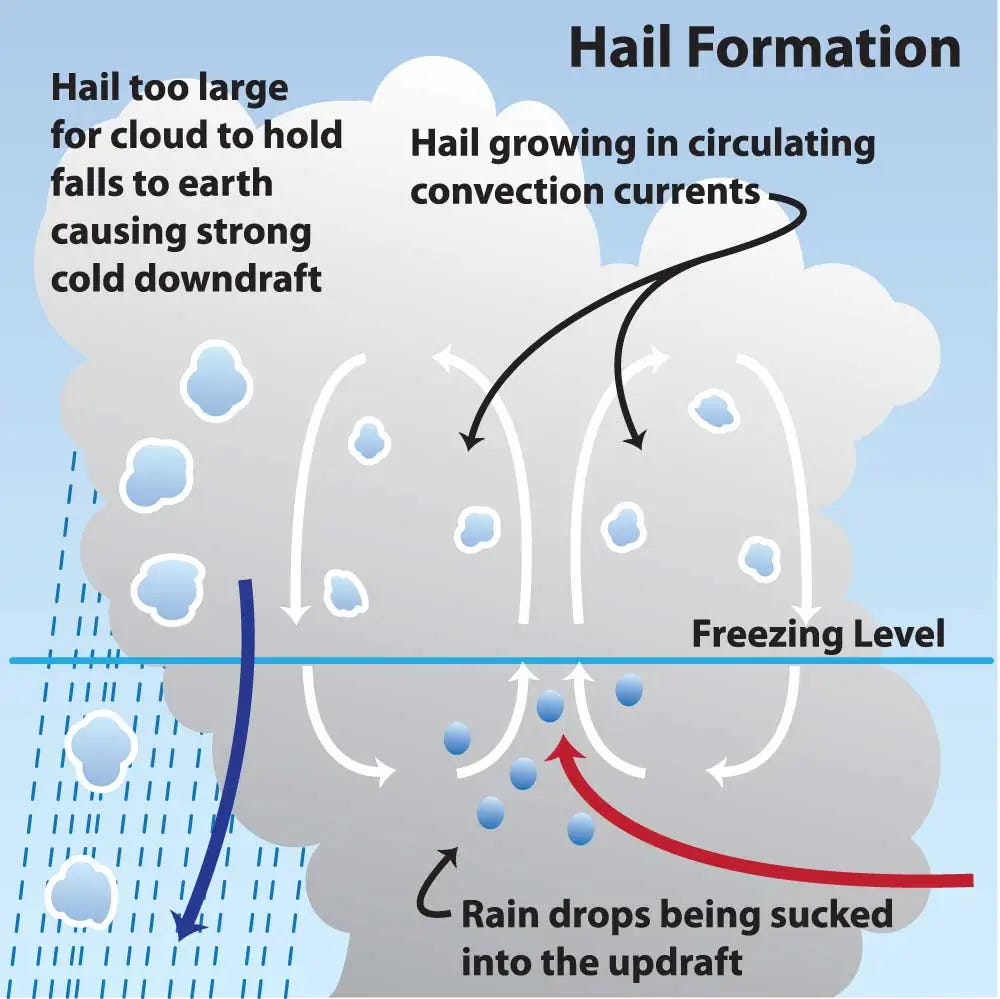

Thunderstorms breathe. They have updrafts, drawing air up into the storm, and downdrafts, exhaling that air back to the ground. In a well-developed thunderstorm, those updrafts rotate, sometimes slowly and sometimes intensely depending on wind shear and storm maturity. Water droplets that find their way into an updraft can get forced up and over the freezing level, and when they do, they become tiny ice pellets. They will fall again, and if the updraft is strong enough, get lofted again above the freezing line, and a new layer of ice freezes over that first pellet, that first seed of the hailstone. Over and over the process repeats, until the hailstone is too large to be suspended in the updraft, the gravitational pull on its weight exceeding the lifting power of the updraft. It falls all the way to the ground. Stronger updrafts can support larger hailstones. Other factors determine hail size, too, including the temperatures from the ground up through the updraft of the storm and the relative humidity (wet and dry layers) up through the storm.

Fun fact: if you slice a hailstone in two, you will see the layers, especially with a larger stone.

Hail often falls fairly close the updraft of a storm, especially the largest hail. For well-formed supercell thunderstorms, the updraft area is often evident as a flat, rain-free cloud base that is flanked or surrounded by rain. The biggest hail will be very close to that updraft, in a swath that is often just a mile or two wide (maybe bigger for those extra juicy storms that have a larger updraft, with angry swoosh of pink, purple, white, and/or red, depending on the color palette of the radar you’re seeing.

Because of the way the ice layers form and the hailstone rises and sinks, hailstones are often not spherical, especially larger ones. They’re oblong, longer on one axis than the others, like an egg or a football or a crazy D&D dice set. They can be spiky as ice crystals form on ice balls. They can be stuck together as they fall, and stones can bust apart as they smack the ground. They can be kind of soft or super solid. Hail is always measured on its longest axis, so if it is 2” long and 1.5” wide, it would go in the records as a 2” hailstone. For very large hailstones, record keepers will often note the weight and circumference (on the widest part of the stone), in addition to its diameter.

Severe Hail

The National Weather Service issues severe thunderstorm warnings when a storm is expected to produce hail that is 1 inch or larger in diameter. Hail stones 2.75 inches (baseball size) or greater are considered “destructive,” and if a severe thunderstorm warning contains hail that size or larger, some locations may actually sound sirens for it.

If you get hail in your backyard, it is very helpful to report it to the National Weather Service. Find the largest stone, measure its diameter at its widest part, and take a picture if you can. The most helpful way to do this is to take a picture of it next to a ruler, like your kid’s 12-inch school ruler or a tape measure. If that’s not possible, take its picture next to any object that is a known, consistent, and measurable size, like a piece of paper or a business card or a dollar bill. If none of these is possible, estimate its size as close as you can in comparison to object with known and standard sizes, like coins and sports balls (check out the image above).

You can report the hail by posting it on Twitter/X and tagging your nearest NWS office, or finding your NWS office’s Facebook page and either sending a message or replying to one of their posts. Always include your location, when the hail fell (not when you measured it, because HOPEFULLY you listened to my advice earlier and grabbed it some time AFTER it fell!), and the size you measured or estimated, and include a picture if you took one. Try to send the report as soon as you can after you measure the hail.

It’s not just for social media glory. Reports like yours help the NWS compare the radar they’re seeing to what’s falling on the ground so that they can issue more accurate warnings during that same event. The reports are collected by NWS as part of the record for that storm, then archived by the National Centers for Environmental Information, available to anyone from researchers to insurance companies. I say with all sincerity that your hail observations are important, valuable, and deeply appreciated.

This Month in Wilder Weather History

April 12, 1945: A tornado strikes Mansfield, Missouri, knocking down trees on the Rocky Ridge farm of Laura and Almanzo Wilder. The tornado was rated F3 on the Fujita Scale and had a path from near Bradleyville to Ava to Mansfield. Their tornado was part of a larger outbreak across the Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, and Illinois, including an F5 tornado in Antlers, Oklahoma, and several F4 tornadoes. No fatalities (20 injuries) occurred in the tornado that clipped the Rocky Ridge farm, but 119 people died in tornadoes during the outbreak. The death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the same day overshadowed the tornado outbreak and its devastation in news coverage.