How can something as slippery as ice get so stuck?

Maybe you’ve taken a child or grandchild to a children’s museum - the kind that encourages hands-on activities. The museum usually has a water table with flowing water from one end to the other, duckies or balls to float on the stream, and rectangular drop-in slats to divert or obstruct the flow. Water can build up behind the obstacle until it reaches the overflow outlet and spills around the obstacle, or a child pulls out the obstacle and releases the flow of water.

Maybe your experience with an ice jam is a little more messy. You want to pour ice water from a pitcher at a restaurant, but it’s thick with ice. A trickle of water makes it to your glass, and then the flow stops as ice clogs the spout. Water spills over the side of the pitcher instead of through the spout, finding the easy way out of its container. Or perhaps you nearly finish your pop/soda or cocktail on the rocks and tip the glass back to get those last few drops. Nothing comes out at first, and then the ice crashes down onto your nose and cheeks, the last few drops released along with the back flow of all the ice in the glass.

The principle is the same as ice clogging up a flowing river, holding back the flow until the pressure bursts through or the water finds a way around.

Ice Jams, Ice Dams, Ice Gorges, and Flooding

Folks who live along rivers in the icy northern U.S. are not strangers to ice jam flooding, the ups and downs of river levels as ice gives way to water.

Ice jams occur during both freeze-up and break-up of ice, but they’re more common at break-up. The wintry lid of ice across a river does not melt smoothly and evenly, like ice cubes in a glass of tea. Ice breaks apart into chunks as it melts and flows downriver. Or perhaps melting snow and falling rain lift the water level of the river, displacing the ice that was in it in large sheets that break up reluctantly as they move downstream. Chunks of ice bash into each other and any obstacles in the river.

Sometimes the ice chunks encounter an obstacle, like ice cubes stuck behind the narrow spout at the end of a pitcher. The obstacle could be a bridge, a bend in the river, a shallow area, a tree fallen across the water. A few get stuck, then more as the chunks can’t get past the congealing mass of river ice. The ice forms a dam, much like a beaver’s dam. Water rises behind the ice jam, putting pressure on the jam, and water levels fall downstream of the jam as the flow is held up by the temporary dam. In fact, falling river levels during ice break-up are a warning sign of an ice jam upstream. The pooling water behind the jam can spill outside the river’s banks, encroaching on roads and homes, fields and forests.

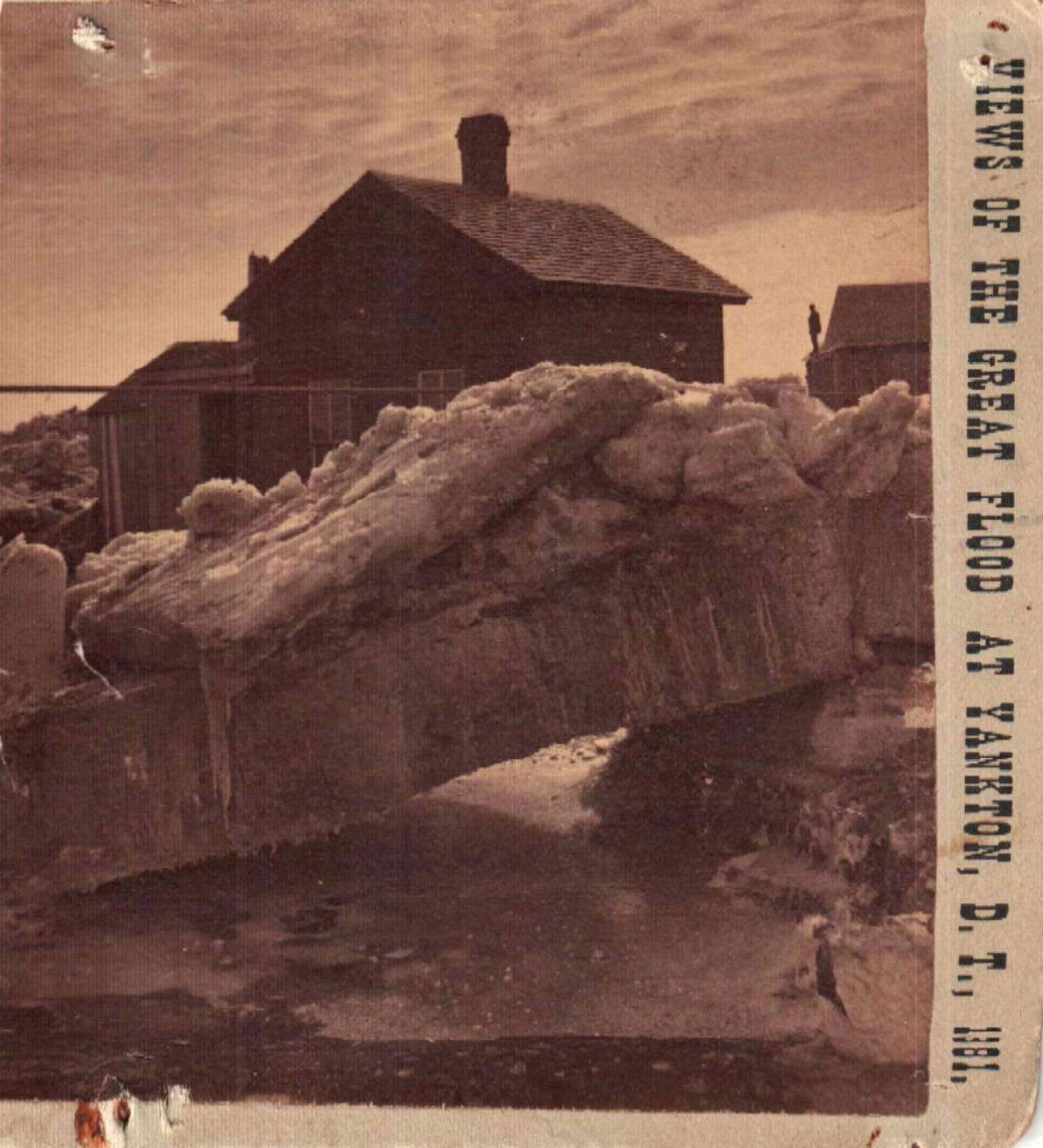

Inevitably, the ice jam must give way. It might melt, or it might collapse under the pressure of water behind it. It might break down piece by piece or all at once in a rush. If the ice dam collapse is abrupt, like the ice jam at the bottom of a drinking glass, the ice chunks surge downstream on the flow of freshly released river water. The surge, along with the abrasive ice chunks (sometimes called an “ice gorge”), can itself cause damage downstream - short-lived but high-impact flood waters, with the ice chunks causing erosion, damaging pilings and docks, and carrying debris with them downstream.

Because ice jams and the resulting floods are destructive, water management agencies sometimes take steps to prevent or release the jams. They might sprinkle dark, dusty material - coal dust, sand, dirt, or ash, for instance - on the ice to encourage it to absorb the sun’s warming radiation, hoping to melt it faster. They might use chainsaws, heavy equipment like backhoes and excavators, or even dynamite in more dire situations to break apart ice. In both cases, the intent is to help the ice release intentionally and more gradually, lessening the risk of an onrush of flood waters due to sudden break-up and clogs, while also providing a release of water from the backed-up flow behind the ice jam. Water management agencies also can place ice booms, pilings, and other objects to catch and slow the flow of ice in intentional locations to prevent more destructive jams downstream.

Laura Ingalls Wilder didn’t mention the ice jam floods in The Long Winter, probably because she didn’t live close to a river and witness them herself. In March of 1881 (the tail end of the Long Winter), as warmer weather reached the Dakotas and some melting began, rivers thick with ice from the unrelenting cold and length of the winter took on water. The ice cover lifted, broke apart, and traveled downstream, clogging easily at the bends and bridges of the rivers. Ice jams in late March and early April of 1881 destroyed homes, shops, bridges, and entire towns along the length of the Missouri River, first in South Dakota, then between South Dakota and Nebraska, and then along the border between Nebraska and Iowa. Scars from the ice jam flooding lie permanent today, from the rather benign-looking Lake Manawa in Council Bluffs, Iowa (an oxbow lake separated from the river during the 1881 floods), to the historical marker directing viewers to the site of Green Island, Nebraska, a town in the shallows of the river swept away in 1881 and never rebuilt.

Flooding also continued a while longer due to the overwhelming amount of melting snow, but that’s another story.

For further reading, try “Gorging Ice and Flooding Rivers: Springtime Devastation in South Dakota,” by Herbert T. Hoover, John Rau, and Leonard R. Bruguier, published in South Dakota History in 1988.

This Month in Wilder Weather History

March 28-30, 1881: Ice jam flooding on the Missouri River inundated the town of Vermillion, South Dakota, with up to 10 feet of flood waters, destroying two-thirds of the town. Ice jam flooding on several rivers in eastern South Dakota and surrounding regions had begun as early as March 12 as brief mild weather started the snow melting process. On March 29, an ice gorge swept away the town of Green Island, Nebraska, which was located in the river bottoms near Yankton, South Dakota. Waters also rose several feet in Niobrara, Nebraska, inundating homes and businesses. Vermillion and Niobrara both were relocated to higher ground after the floods of spring 1881. Residual ice jam flooding lingered into early April.