Many of you know that chasing storms is a hobby of mine. I’m no wild cowboy like that dude in the movie Twisters, driving into tornadoes and shooting fireworks. We are more cautious, more measured, preferring to observe the big storms and tornadoes from a distance that lets us appreciate the view of the storm. We have no desire to be in the path or get the closest shot of the storm. And honestly, staying out of the way of a tornado is relatively easy, as long as a chaser understands the storm’s motion and behavior and pays attention to the road network to make sure there is a safe path away.

The tornado is not the part of the storm that scares me the most.

It’s the lightning.

I’ll stand and watch a tornado with little fear for my immediate personal safety, but if a dagger of lightning darts out of the sky within a few miles, I’ll be dashing into the car and rolling the windows up faster than you can say “electric.” I don’t mess with lightning.

By definition, all thunderstorms contain lightning, whether they are producing tornadoes and large hail, a light shower, or no rain at all. While the path of a tornado can be detected and, to some extent, predicted, the location of the next lightning strike is far less predictable. Lightning can strike in the heart of the storm or twenty miles away from it. Predicting the first lightning strike from a developing thunderstorm is especially challenging.

Let’s raise our lightning literacy!

Lightning Types

Cloud-to-ground lightning

Lightning strikes that extend between the cloud of a thunderstorm and the ground (or a structure on the ground) are called “cloud-to-ground” lightning. As you can guess, these are the strikes that pose a danger. Lightning strikes cause injuries and deaths to humans, livestock, and other animals. They can cause house fires, tree damage, power outages, and electrical surges that fry the electronics in a home even when it is not directly struck.

Cloud-to-ground lightning can produce brilliant, photogenic displays of forked channels visible for miles through the night sky. Or, the strikes can be masked by pouring rain, the channels hardly visible except for a diffuse but bright flash of light. Storms can produce continuous lightning for hours or just a flash or two. The lightning and thunder from a storm may announce its arrival an hour before the storm arrives, or the lightning and thunder may begin when the storm is right on top of you. Dying storms might seem to be done, then produce one last flash.

Lightning does not confine itself to areas where it is raining. “Dry lightning” is more common in the western United States, with lightning striking from tall clouds even when the atmosphere is too dry for rain to penetrate. Even with a rain-producing thunderstorm, lightning can strike far from the rain. It is not uncommon for lightning to strike 10 to 20 miles outside of the rain core of a thunderstorm, often striking ground ahead of the storm from the high-level anvil clouds.

Cloud-to-cloud and intra-cloud lightning

Most lightning does not strike the ground. Instead, it flashes through the cloud of a thunderstorm (intra-cloud) or between thunderstorm clouds (cloud-to-cloud). Some of the most brilliant lightning displays, especially in the central U.S., are “anvil crawlers,” passing through the high clouds around a thunderstorm in brilliant branches overhead. Intra-cloud can illuminate a distant, isolated thunderstorm all the way to its top. Developing thunderstorms often produce intra-cloud lightning before the first cloud-to-ground strike, the low rumble a warning to get to shelter before the danger begins.

Heat lightning

Have you ever sat outside on a warm summer night in a dark place, watching reddish flashes of lightning on the horizon? You may have heard this called “heat lightning,” occurring in mid-summer with its warm orange and reddish colors. Heat lightning, it turns out, is simply very distant lightning. Just like the sun turns orangish and reddish as it sets, lightning that is far on the horizon can take on reddish shades as the light passes through the atmosphere

Lightning Safety

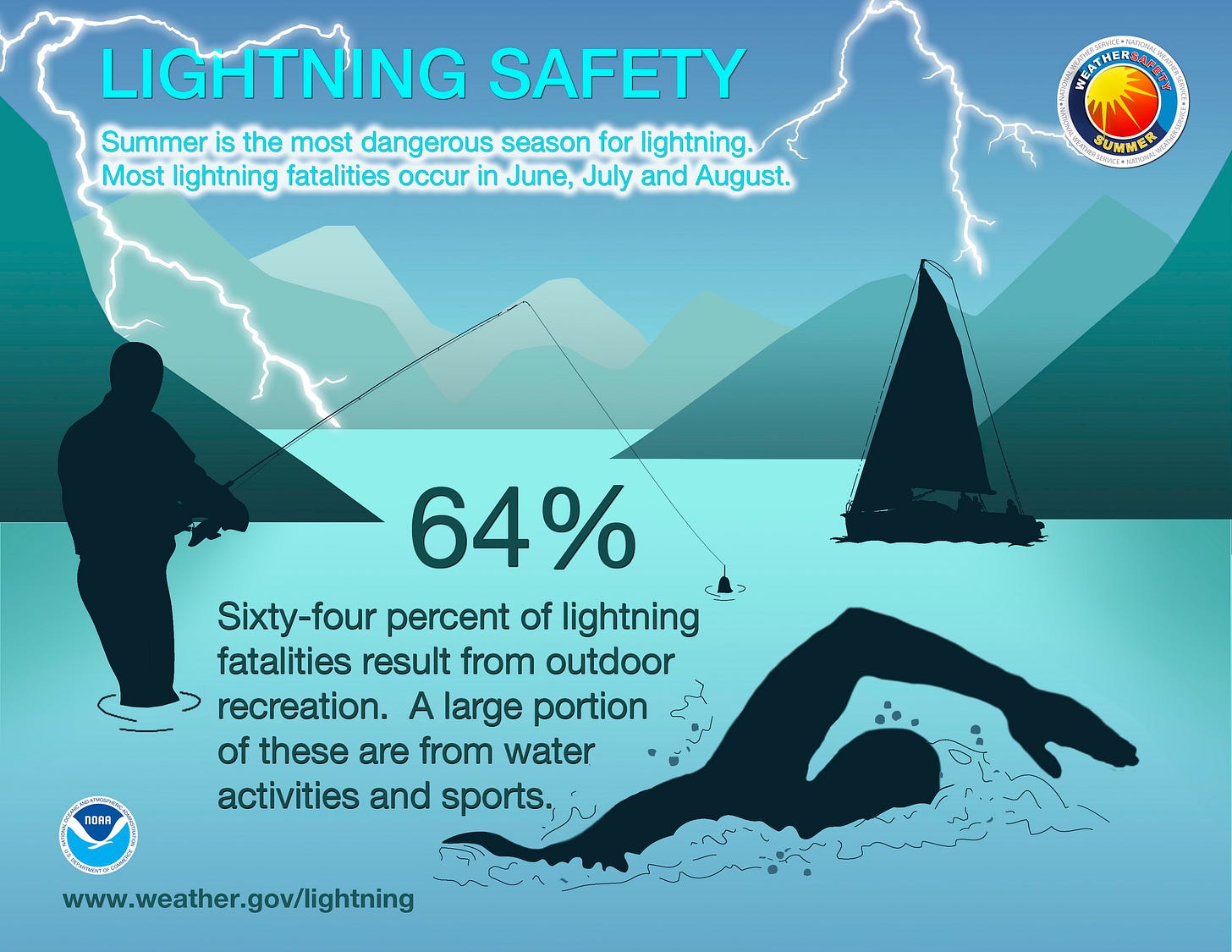

Lightning kills an average of roughly 40 people per year in the United States. Lightning kills about 10% of the people it strikes, with the other 90% left with injuries ranging from relatively minor to serious and disabling. And sorry, guys - men are four times as likely to be struck by lightning than women!

Working and playing outdoors are big risk factors, of course. Almost two-thirds of lightning deaths occurred while people were fishing, boating, playing sports (such as golf, soccer, running, hiking, baseball, and football), and beaching. Fishing is by far the riskiest activity for lightning, followed by beach activities, camping, boating, and riding ATVs or motorcycles. Yard work and mowing the lawn account for a handful of lightning deaths, as well. Meanwhile, nearly 20% of the fatalities were among folks working outdoors, with farming and ranching the most common victims among outdoor workers.

Lightning strike injuries and deaths peak in the summer - July, June, and August (in that order) rank as the top three months. Lightning injuries and deaths are more common on the weekend than during the week, as people take to the outdoors for their recreation.

The best way to avoid being struck by lightning is, quite simply, to head indoors. Get to a closed shelter (not a picnic shelter or other open structure) as quickly as possible when you see a flash or hear thunder. A car or other vehicle does provide safe shelter as long as it is fully closed (no open windows/doors or soft tops).

Sometimes, though, safe shelter is far away. If you have plans to go out boating, it is imperative that you be aware of the weather forecast and observe the skies for signs of thunderstorms developing, so that you have time to reach shore safely.

There is no safe place outdoors during lightning, but there are things you can do to decrease your risk and exposure. Get out of and off of water immediately (including lakes, ponds, and pools). Get off of exposed landscapes like hilltops, ledges, or peaks, and get off of and away from tall structures like towers, open farm equipment, goal posts, fences, and windmills. And you’ve probably heard this before, but never take shelter under tall or isolated trees. Make yourself smaller by crouching down, but don’t lie flat on the ground - a nearby strike could pass from the ground through your body.

To judge how far away lightning is, a rule of thumb is to count the number of seconds between the flash and the boom, then divide by five to gauge how many miles away the lightning is. So, if you count to 10, the lightning is 2 miles away. If you count to 2, it is less than half a mile away. Follow the 30/30 rule for safety: if you count 30 seconds or less between flash and boom, get indoors, and wait 30 minutes after the last strike before returning to outdoor activities.

Lightning First Aid

If you witness someone being struck by lightning, call 911 immediately - time is essential. The body does not carry an electrical charge after the strike, so you can immediately begin first aid support, if you are trained and able. If the victim is unconscious, check for a pulse and breathing, and if you cannot detect both, administer CPR. If the victim is breathing and has a pulse, check for injuries such as burns that may require immediate first aid, and keep the victim lying down until paramedics arrive. Even someone who appears to be uninjured should be checked by medical professionals after a lightning strike, as some injuries could go unnoticed, and should be kept still until paramedics arrive.

For more lightning first aid information, follow this guidance from the Red Cross.

For more lightning safety information, check the National Weather Service and the Centers for Disease Control.

This Month in Wilder Weather History

June 6-8, 1931: Published in A Little House Traveler, Laura kept notes from the journey she and Almanzo took into South Dakota for Old Settlers Day. On June 11, Laura wrote as she passed from just north of Yankton through Howard to De Smet, “Crops look good in spite of freezing ice three nights last week.” Weather records do not support true freezing conditions, but on June 6-8, low temperatures dipped into the 40s across eastern South Dakota. June 7 was the coldest morning, with widespread temperatures around 40-42 degrees.

Wilder Weather Preorders!

Preorder your copy of Wilder Weather: What Laura Ingalls Wilder Teaches Us About the Weather, Climate, and Protecting What We Cherish from the South Dakota Historical Society Press. And for those attending LauraPalooza in July in Sioux Falls, don’t forget to leave a note!